Many research labs across the country use animals for testing products such as make-up or medicines. For the past decade, advocates have pushed to get more of these animals — especially research dogs — adopted after they are no longer needed. Just a handful of states have policies in place. Illinois just recently joined that list.

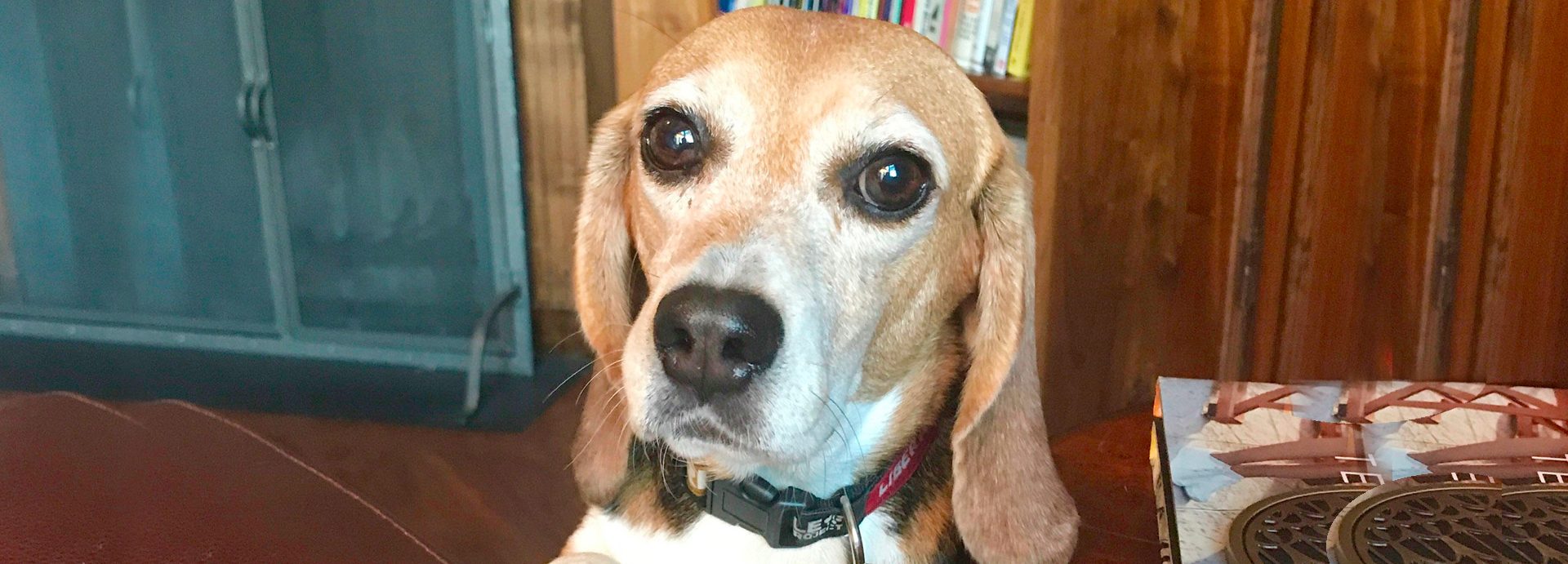

Lucy is a three-year-old beagle who grew up in a research laboratory. Last year, she was rescued by the California-based organization the Beagle Freedom Project who paired her up with Lauren and Scott Knudsen of Winnetka, Illinois.

Lauren says the labs agree to release research dogs that are no longer needed as long as no information is linked back to the facility. “For almost all of the dogs that get adopted, you’re not told anything. You don’t even know what they were being used for, what they were tested for, you have no idea,” she says.

The secrecy also means some dogs come out with medical issues that can’t be traced to their source. Lucy, for example, arrived with seizures and damaged vocal cords. The rescue beagle can’t bark like her family’s two other beagles, Wendy and Tanner, and she must take seizure medication. Lauren and Scott say they believe Lucy was hurt during her time in the lab.

But these “medical surprises” did not stop them from keeping Lucy after they agreed to foster her.

According to the Beagle Freedom Project, about 65,000 dogs are used in U.S. laboratories each year. Most of these dogs are beagles, used extensively in research for their docile nature. Some 2,000 cats are also used each year but not many make it out alive after each procedure. When the dogs or cats are no longer needed, it’s difficult to track their whereabouts: many are euthanized and not many given up for adoption. That’s where the group comes in to talk labs out of euthanizing the animals.

While these “rescue events” help place these former research animals into homes, advocates say policies are needed to further encourage labs into giving their animals up for adoption on their own. This is what happened in Illinois.

For two years, the Beagle Freedom Project pushed to garner support from lawmakers in Springfield. Democratic Rep. Linda Holmes of Aurora became the “Beagle Freedom Bill” chief sponsor. The measure called for labs using any tax-payer funding to reach out to animal rescue organizations and place cats or dogs into appropriate care.

But Kevin Chase, the Beagle Freedom Project’s vice-president, says many research labs opposed the legislation and slowed down the measure’s progress in the General Assembly. He says the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign was a strong opposing voice.

Robin Kaler, the university’s spokesperson, says the university always had an adoption policy in place and the law wouldn’t apply to them. But she does agree the measure’s original language may have exceeded authority by asking for all types of animals to be released, as well as not allowing each facility to set its own adoption policy guidelines.

Chase says the final measure limits the animals to cats and dogs and allows facilities to write-up their own adoption policies. The university then removed its opposition. “That’s the reason why the bill passed,” Chase says. The law went into effect earlier this year, making Illinois the sixth state in the country with such policies.

Lauren and Scott made sure to include Lucy in their trips to Springfield last May to meet with lawmakers, just as the final round of voting was due to take place. Other beagles across the state also made the trip.

“Unless you actually see the beagles, meet the beagles— it’s hard to really understand what this is all about. Definitely more powerful if the different politicians we’re meeting with actually get to see the dog,” Scott says.

Almost a year after Lucy joined their family, Scott and Lauren say all that remain are the physical reminders of her time in the lab — such as the identification number tattooed on her right ear, the seizures that have become less frequent over the last few months, as well as her small size.

“She’s a little smaller than most beagles, she’s a little bit more petite. We kind of say she still looks like a puppy,” Scott says.

“She’s very high energy, she’s very curious, friendly and outgoing. But she has this darker, this mysterious side to her you can’t quite put your finger on — that occasionally shows up and always reminds us of the lab. But she is a really, really sweet dog.”

Original Article: NPR Illinois